The Overhang 2.1 - Halfway(ish)

Ka mua, ka muri – looking backwards to look forwards: what past governments' polling performance can tell us about the possible futures of the Sixth National government.

Kia ora, happy new year, and welcome back.

We’re using the start of the new (political) year as an opportunity to look back on the polling performance of the Sixth National Government so far, how it compares to past administrations, and where things might go.

The tl;dr version

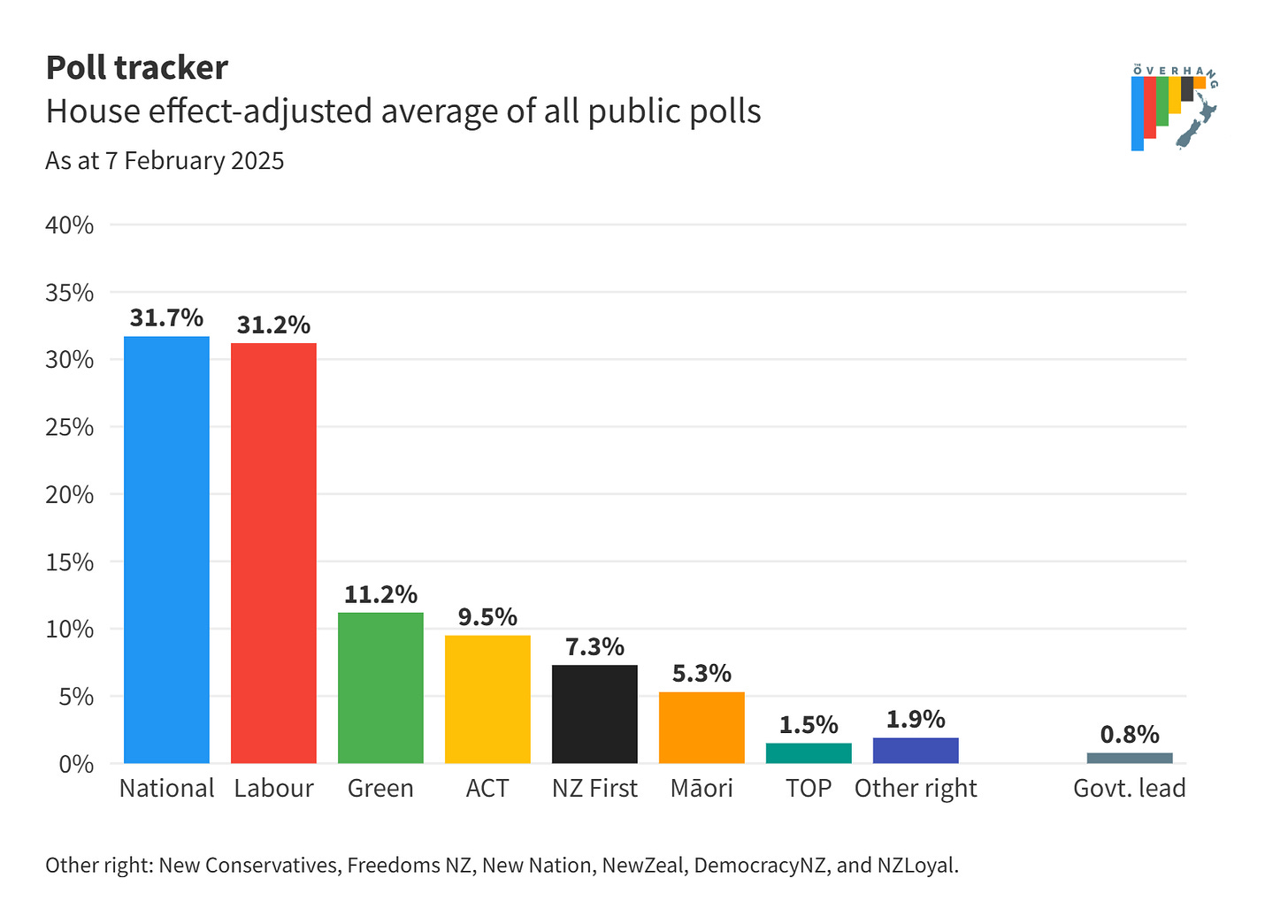

A little under halfway through the term, the government parties have a combined +0.8% lead over the opposition.

This is below average compared to all government terms this far in (2.0%) and well below the average for a first term government at this point (6.2%).

The two first-term governments who were performing similarly (Kirk and Bolger) also faced significant economic challenges.

One went on to lose, the other to (very narrowly) win.

Recoveries are possible, but second terms are not a given – even for National.

Halfway(ish) through

Nearly halfway through their term, National and its support parties hold a narrow polling lead over Labour and the other opposition parties. National sit on 31.7%, ever-so-slightly ahead of Labour on 31.2%. Coalition partners ACT (9.5%) and NZ First (7.3%) combine with National to put the government on 48.5%. Combining Labour’s numbers with their likely support partners the Greens (11.2%) and Te Pāti Māori (5.3%) gives the opposition 47.7%. On net, this is good for a 0.8% government lead.

How we got here

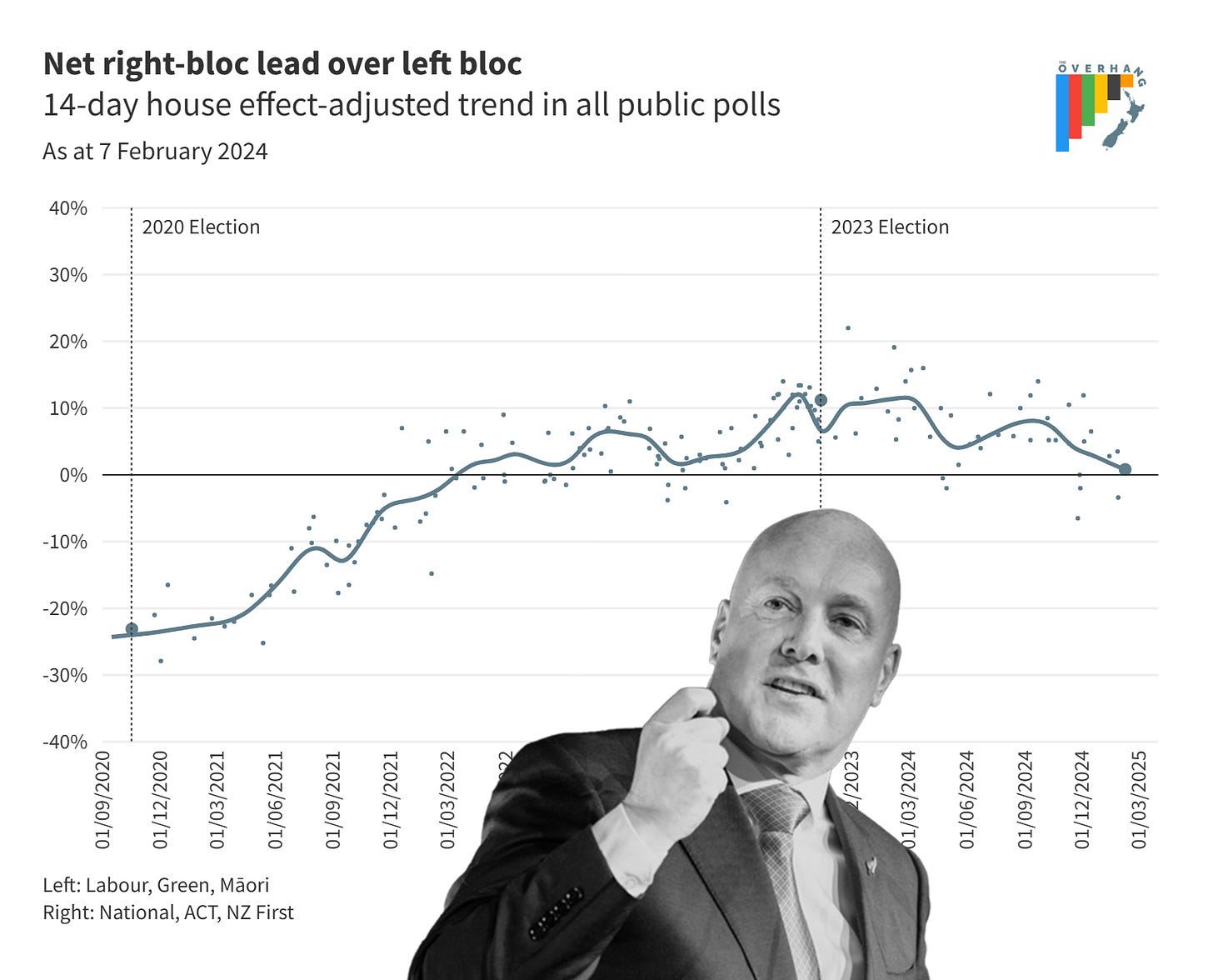

After winning the 2023 election with an above-average 11% margin, Luxon and co initially maintained a similar lead in the polls. From about the middle of 2024, this dropped back to around 5%. However, through the back end of 2024 and into the new year this has decayed to just the abovementioned 0.8%, with the opposition even taking a lead in some polls.

On the face of it this is… not great. To be secure in re-election, you would want to be doing better than a statistical dead heat. At the same time, the government would still cling to power on these numbers and there’s a while to go before the next election, so we shouldn’t over-read these trends.

But this doesn’t exactly feel like a freshly-pressed government basking in the long summer days of a waning honeymoon. As we’ll see below, if anything it resembles either a second term beginning to stall out and go stale, or more to the point one of a couple of seemingly-doomed first term government struggling to get traction amid economic chaos.

Some history

But how bad is it really? To put the sixth National government’s performance in perspective, we can compare it to past governments at approximately the same point in the electoral cycle.

(This analysis is deeply indebted to the diligent work of Patrick Leyland of The Progress Report for compiling polling data prior to 2002 – a massively invaluable resource for anyone doing political science in Aotearoa).

This chart shows a rolling average of the government’s polling lead over the opposition for each of the electoral cycles for which we have data. A positive figure shows the government leading, a negative figure shows them trailing. The dots at either end show the result of the elections.

From 1990 onwards (as the FPP system began to break down and was replaced by MMP) it also shows the difference between the left and right blocs (in paler red/blue).

The dashed lines highlight where past governments were sixteen months into their terms: the same point the Luxon administration is at now. Zooming in on this point in time we can get a sense of how today compares to various yesterdays.

While below the all cycles average of 2%, Luxon’s position is by no means disastrous: especially compared to the pits of popularity that governments of both hues experienced in the 1980s and 1990s. He’s no John Key (we knew that already) but he’s also not second-term Lange.

However, a government’s popularity tends to decline over its lifespan. Isolate just first terms, and things look worse for the current government.

Most first-term governments experience an extended honeymoon (+6.2% on average). While not as commanding as Clark or Key’s double-digit leads, Muldoon, Lange, and Ardern all retained reasonable goodwill and went on to second terms.

And it’s worth noting that this isn’t a case of a narrow initial win putting the current government off to a bad start: the 11% margin at the 2023 election is above the historic average of 8%. Both the current level and the declining trend to get there are out of step with the historical norm.

Of the first terms for which we have data, the two who were performing like the current government were Norman Kirk’s third Labour government in the mid-1970s, and Jim Bolger’s fourth National government in the turbulent early 1990s.

A departure from the historical (Big) Norm

Kirk’s government had taken power with a respectable if not earth-shattering +7% win over Jack Marshall’s National (who were at that point four terms deep into a Natural-Party-of-Government imperium).

After a year of governing, the shocks of the 1973 oil crisis and Britain’s accession to the European Economic Community helped reduced this to little better than an effective tie with the as-yet still Marshall-led National. Subsequent events – Robert Muldoon’s takeover and Kirk’s near co-incident death – would see Labour go on to defeat under replacement leader Bill Rowling.

The Mother of All Comebacks

By contrast, Bolger had won in a +13% landslide over world-historic hospital pass recipient Mike Moore. But then the aftermath of the Mother of All Budgets, the supertax reversal, and sundry other economic crises saw a complete collapse to -11% behind Labour (an almost difficult to comprehend -24pp reversal.) Factor in the rising popularity of the nascent Alliance, and National were a catastrophic -28% behind the combined opposition. Moore – whose position Hipkins in some ways resembles – looked certain to return to power.

But then he didn’t. Unlike Rowling and thanks to the split on the left in the final FPP election, Bolger was able to claw back by the barest of margins (literally a zero-seat majority before a Labour dissident took the speaker’s chair) and held on in 1993.

… but it rhymes

The common thread between these two cases – one that is shared with the current government – is economic strife. The current recession (so far) is yet to reach the retching depths of the 1970s and 1990s, but doubtless Luxon’s fortunes will be influenced by the recovery (or lack thereof) of the economy.

Luxon’s situation looks to be significantly better than Kirk/Rowling’s: Kirk’s death was an unaccountable tragedy, and the opposition seem unlikely to replace its previously-defeated leader with a pugnacious bruiser in the Muldoon mould. Disquieted as the global trade situation is given the Trump administration, it’s not quite dealing us the bodyblows that the loss of the British market to the EEC did.

As spelled out in greater depth by Henry Cooke, there are closer similarities to Bolger’s position. Like Moore, Hipkins has stayed on. The left is again displaying fissile tendencies (the Greens’ support remains stable and Te Pāti Māori’s has risen on the back of opposition to the Treaty Principles bill) but this won’t help in an MMP contest. Somehow – defying the logic of actuarial tables and the space-time continuum – like Bolger Luxon faces the risk of Winston Peter’s acting out. Most importantly though and despite the historical rhymes, Luxon has a significantly smaller hill to climb than Bolger did.

Early on-set second term-itis?

The government’s performance thus far might be middling compared to most first terms, but it is better than the truly dire examples Kirk and Bolger provide. If you squint a bit, the current slide to a narrow lead does not look out of place beside governments in their second terms.

Muldoon was 5 points ahead, although this may be a case of the polls flattering him given he undershot them by about that much in both 1978 and 1981.

At this point in his second term Bolger sat -7% behind the combined strength of Labour and the Alliance – which by his standards was a massive improvement: an improvement that would continue in the run up to 1996.

Lange and Ardern were both half-way through precipitous flop eras that would end in eventual replacement and defeat. Clark too was beginning her Ōrewa-induced slide – albeit one her government would recover from.

Even the seemingly invincible John Key was struggling at this point in his second term. While National held a respectable lead over Labour, its lack of dance partners briefly put it on level terms with Labour and the Greens combined.

All these National governments went on to a third term while only one of the Labour ones did.

Always remember that you are mortal

It’s tempting to read this as reinforcing National’s “natural party of government” invincibility. I think that’s a mistake. While true over the Holland and Holyoake post-War boom years (largely outside the scope of this piece given the lack of polling data), between 1972 and 2005 National and its allies only won the popular vote 3/12 times (1975, 1990, and 1996).

Despite an initial burst of popularity Muldoon would go on to lose the popular vote twice: propped up by FPP and – if you want to describe it charitably – a favourable electorate redistribution in 1977 (gerrymandering, if you want to be less charitable).

Bolger’s second majority was jerry-rigged together with duct-tape (speakership deals) and bits of string he found behind the couch (the United party rebels, Ross Meurant).

The Key years look like a restoration, but that can equally be viewed as part of the stable three-term turnabout ushered in by MMP and the benign macroeconomic environment at the end of history. This context also benefited Labour in government. The nine-year pattern – as previously noted and subsequently validated by Labour’s 2023 loss – has begun to fall apart.

Where to from here?

If you’re a government supporter looking for cope:

Things aren’t as bad as they could be (your guy isn’t 30 points down).

Governments have come back from worse (the guy who was won).

Conversely, if you’re an opposition supporter looking for cope:

This is pretty bad for a first term government.

The previous two times a defeated Labour PM stuck around, the opposition won the popular vote.

Finally if you’re a pure and objective centrist (or just generally checked out and indifferent):

The polls as they stand are finely balanced.

Assumptions about natural parties of government or stable multi-term cycles are outdated.

I’m conscious that this was a very long-winded way to say “National could win in 2026 but on the other hand they could lose”. Hopefully this helps guard against conventional wisdoms or confident predictions.

The uncertainty is the point.

Ka kite (hopefully) anō.