Kia ora

Welcome to Issue 1.1 of the Overhang I guess?

I had planned to do some kind of proper introductory post. To lay out what my goal is with all this and what you can expect. But that was too much like hard work. Something else grabbed my attention. So we’re starting here.

tl;dr

Support for the minor parties is historically high. The gap between Labour and National is historically low. This is historically unusual.

The last time this happened was the late 1990s, in the early days of MMP. Those elections (1996 and 1999) came after a period of upheaval and radical change, but were then followed by a period of major party consolidation.

Ultimately, 1996 and to a lesser extent 1999 are better templates for the 2023 election than 2002 or 2005.

Chaotic coalitions

Both commentators and politicians have been calling out coalitions of chaos or of cuts or of colonisers. Support for the major parties remains low, and the outcome of the election remains in doubt. This isn’t unusual. It’s an election year. Even after 30 years, people still pretend not to know how MMP works.

I’m not the only one to have noticed this (four people did while I’ve been working on the draft) and it’s kind of…meh.

But the thing is we’re not wrong to notice something's up.

Both the left and the right can credibly claim their opponents might form a government of three or more parties, and with significant minor party representation. This is unusual. It’s only really happened twice before and is the jumping-off point for this post.

Where we are

Since the ascension of the two Christophorae, polling has settled into a stable pattern:

The gap between Labour and National remains low.

The share held by minor parties remains high.

Post-Luxon, the gap between National and Labour has averaged a little over 3%. Post-Hipkins, it has averaged just 1%. This is well below the long-run average of 12%.

Over this whole period, the share held by minor parties has averaged around 30%. In recent months it has climbed as high as 35%. This is largely on the back of respectable numbers for ACT, the Greens, and more recently Te Pāti Māori (but with a non-negligible share taken by the rest). Again, this is above the long-run average of 22%.

On their own neither of these situations is novel or interesting. National and Labour have run close before. The minor parties have done well before.

What is weird is both happening at the same time.

Boundaries of the chaos zone

I first tried making this point a while ago with a scatter plot comparing the major party gap and the minor parties’ share of polling since the the start of the MMP era.

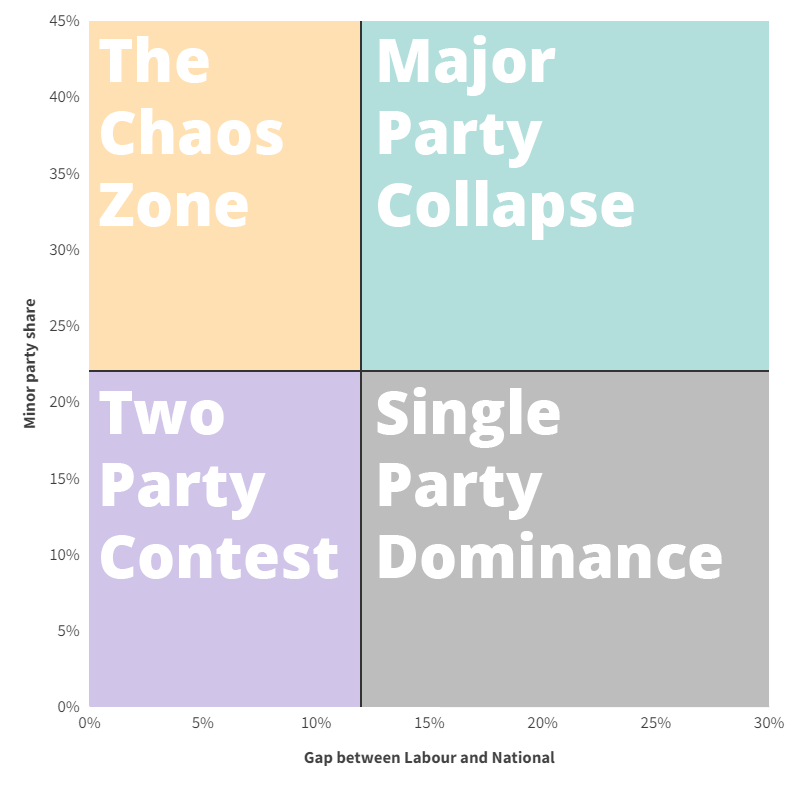

Apparently that was hard to follow. What it does is break the polling space down into four quadrants to help define partisan electoral dynamics at any given point.

The quadrants are, going clockwise:

Major party collapse one of either National or Labour collapsing and shedding support to their opponent and to the minors (above average gap, above average minor share)

Single party dominance one of the majors dominating their opponent and the minor parties (above average gap, below average minor share)

Two party contest National and Labour in a close race at the expense of the rest (below average gap, below average minor share)

The Chaos Zone a close contest between National and Labour, high percentages for minor parties (below average gap, above average minor share)

The right-hand quadrants can be further broken down by which of National or Labour is collapsing/dominating.

The amount of time we’ve spent in each quadrant is not equal. The largest share of the time since 1993 (37%) has been spent in a two-party contest: National and Labour both looking credible and absorbing most of the support. The next most common are phases where either one major party is collapsing (27%) or is sweeping the field (24%).

The rarest situation - and the one we’re in now - is an all-round close contest (14%).

Where we’ve been

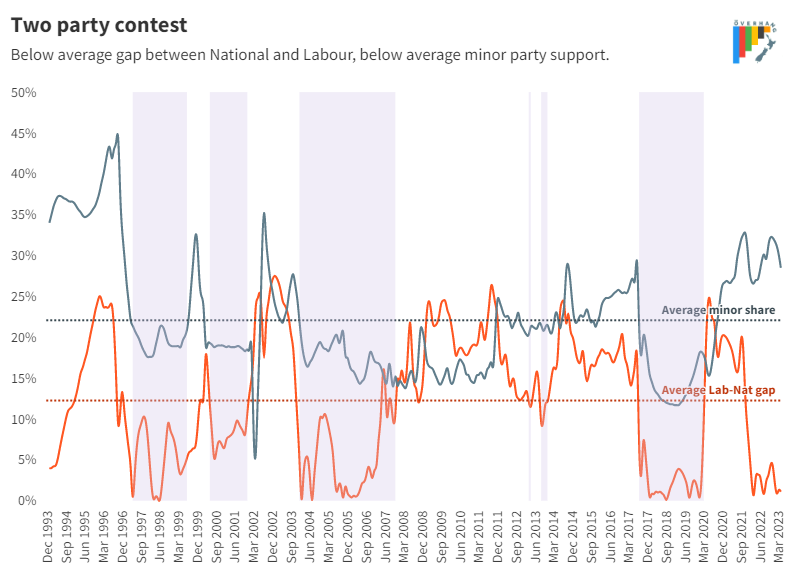

Plotting the data above over time might make things clearer.

Combining this view with the quadrants (or “phases”) above periodises recent political history and the partisan dynamics we’ve experienced.

That’s still too many colours at once, so we’ll take each in turn…

Major party collapse

Starting in the top-right corner, we have periods of major party collapse.

Technically there have been seven intervals of this, but really only four (two for each major party)…

February 1995 - September 1996 The lead up to the 1996 general election, where it really looked for a minute like Labour was going to lose it’s status as a major party, and become just one of several (along with the Alliance and NZ First) opposed to the Fourth National government. Clark’s subsequent rebuild in the final stretch of 1996 and the lead up to 1999 is one of recent political history’s underrated achievements.

July 2002 - December 2002 This covers the 2002 election and its immediate aftermath, after both National’s collapse under English and Peter Dunne’s tango with The Worm. Worth noting (in contrast to the 2020 episode below) that peripheral National support had four places to flee to (Labour, NZ First, United Future, and ACT) rather than just two.

On and off from December 2011 - July 2017 Labour’s Era of Many Davids, from Phill Goff’s defeat at the 2011 election through to the resignation of Andrew Little (spiritually a David). Despite a few glimpses of a close contest, this was a period where Labour shed support to the Greens on the left and to NZ First on the right. Not as dramatic as the pre-1996 edition, but much more extended.

October 2020 - October 2021 The back-half of National’s COVID/Collins collapse, where National remained in the depths, but more to the benefit of ACT than of Labour (as noted, unlike in 2002 there were fewer places for the looser National vote to go).

Single-party dominance

Next up are periods where one of the major parties lords it over everyone else.

Five-ish main instances, and much longer for National than for Labour…

February 2000 - May 2000 The Clark government’s honeymoon period, ended by a period of Shipley revival during the ‘winter of discontent’ (sidenote: what we thought was a serious disturbance in the early 2000s seem so quaint now).

February 2002 - June 2002 The early lead-up to the 2002 general election, around the time of the implosion of the Alliance and Bill English’s well…

December 2007 - November 2011 The Key government’s brief engagement to the electorate and then their long, long honeymoon.

Intermittently from June 2012 - December 2015 The bits of the back-end of the 5NG where Labour were still a basket case, but the minor parties weren’t featuring as much.

April 2020 - September 2020 COVID and all it entailed.

Two party contest

Where we’ve spent the plurality of the time (and where it felt like we were heading post-Luxon until we just… didn’t): acting like it’s still the FPTP days.

Five (but really only four) instances…

May 1997 - July 1999 The lead-up to the 1999 general election where somehow the contest remained close, despite Helen Clark reviving her party’s fortunes, National going through a coup, and the National-NZF coalition blowing up in Loony Toons fashion.

June 2000 - November 2001 The abovementioned false dawn of the second Shipley era, during the early Clark years.

January 2004 - November 2007 Ōrewa to ‘08: the tense end to the Clark years.

Two brief, fleeting gasps in March 2013 and September - December 2013 A short blip where Shearer appeared to be getting his shit together, and then Cunliffe’s early bump after rolling him.

August 2017 - March 2020 Jacindamania through the start of the pandemic.

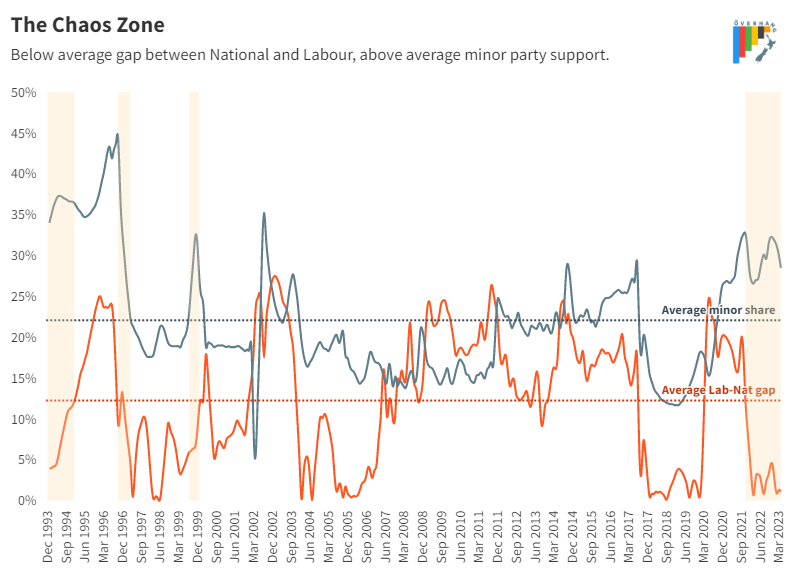

The Chaos Zone

Okay (after a long diversion through a bunch of history that was maybe besides the point but that I find interesting) the actual thing I’m supposed to be writing about.

Things fall apart, the centre cannot hold, the falcon cannot hear the falconer, the old world is dying, the new world struggles to be born, now is the time of backbench MPs acting up and acting out.

November 1993 - January 1995 The beginning of the MMP era. The nation awoke bleary-eyed from the 1993 general election and realised not only had Irish Jim managed to pull it off, but we’d also chosen a new electoral system. Okay in reality this episode was a continuation of the pre-MMP, post Roger and Ruth crack-up of the two-party system. (And yes I know the result wasn’t clear the morning after).

October 1996 - April 1997 A transitional phase after the 1996 general election, as rising support for Labour crossed over with declining support for NZ First and the Alliance. Unclear whether this should really count.

August 1999 - January 2000 The lead up to and aftermath of the 1999 general election where Labour had not yet consolidated the left, with a freshly-independent Green Party and a bloodied but unbroken NZ First asserting themselves alongside the Alliance and ACT.

November 2021 - Present *gestures around*

What does it mean?

Things could get better, or they could get worse. It’s hard to say.

The 1996 and 1999 elections followed a decade of reform, disruption, and austerity. We looked like we were headed down a European path: genuine multi-party democracy, a Pasokifying social democratic party, and a rising populist right.

Low support for the then incumbent National party showed clear dissatisfaction with the status quo. At the same time, the initial lack of a coherent alternative from a Labour party still getting over what they did to themselves and to the country in the 80s meant the major opposition party didn’t benefit.

The electorate were casting about for something - anything - as an alternative. Minor parties rose, fell, split, and merged. The majors cracked-up with defections, in-fighting, and coups (attempted and successful).

Sound familiar?

But then it didn’t happen.

Contrary to a subsequent pattern of major parties shedding support over election campaigns, Labour’s position improved over 1996. Then National stitched together a largely continuity government despite all Winston Peters’ bluster.

Longer term, first Clark then Key forged a modified Westminster equilibrium on the back of a third-way mixed economy powered by the China boom, milk money, and low global interest rates.

So maybe that’s where this goes. Things get better, or at least more Normal. Like Bolger in 1996, Labour keep the nine-year cycle going by cobbling together one more win. Then, after a period of disquiet, one of the majors (probably National, given where we are in the cycle) is able to consolidate around a new set of modifications to the consensus. The institutional fundamentals (more on this in a future post) that dictate a two-and-three-thirds party system will win out.

But maybe they won’t.

Firstly, at a micro level, neither Hipkins nor Luxon seem to have the talents of Clark or Key. The pattern of minor parties rising with greater attention during the election campaign could reassert itself, and we could end up with our most diverse (in partisan terms) parliament yet.

Secondly, there’s no centrist minor party exercising an amphoteric effect on the majors helping to maintain the status quo between governments (unless TOP can pull it off).

Finally, the macro forces of the 2020s and 2030s will be destabilising rather than stabilising. While the Clark-Key consensus was partly down to their policies and personal abilities, it was also a product of the end of history. Hipkins, Luxon, and whoever follows them will not be so fortunate.

Events have and will continue to transpire.

The disruption we’ve seen through the COVID pandemic, supply chain disruption, geopolitical instability, inflation, and now climate emergencies isn’t going away. If the major parties insist things are still Normal, the electorate will look for answers in other (sometimes weirder) places.

All of which is to say:

Congratulations to anyone who made it this far. I didn’t plan on writing 2000 words on this, but we’re a one-man-show, so lack editorial discipline. Future posts will have a shorter, more current-events style focus in the lead-up to October. But I can’t promise I won’t also do rabbit-hole pieces like this one.

Any feedback/critique/character assassination is welcome, I’m still working out what this is for, and what other (more normal) people are interested in.

Ka kite anō (hopefully)

Rustie