The Overhang 2.3: Boundary Issues Part 3

The third part in a series on the upcoming boundary changes, looking at the rules for redrawing electorates and the philosophies than inform their application.

See, I said we would be back soon. (Welcome to neurodivergent hyperfixation week).

Today we continue an unnecessarily deep-dive into the process for redrawing electorate boundaries. Parts one and two dealt with the number of electorates and the broad population changes since 2018. This part looks at the rules of the game.

Parts 4 and 5 will look at how this applies to the adjustments we might see on the ground (a review preview, if you will).

tl;dr version

Electorates should in general be equal to the quota

Electorates must be within plus or minus 5% of the quota

When drawing boundaries, the Representation Commission must consider:

existing boundaries;

communities of interest (including for the Māori seats, communities of interest to Māori (ie: hapū and iwi));

facilities of communications;

topographical features; and

forecast population changes.

These considerations are not deterministic and judgment matters. The Commission faces some high-level choices of ‘philosophy’.

Despite this wide discretion, the Commission (or anyone objecting to or predicting their choices) face unavoidable geographic and demographic constraints.

Statutory criteria

The Electoral Act 1993 sets out what the Commission must or may do, and what they have to consider. The primary considerations are the electorate quota and tolerances (seats of roughly equal size). Secondary considerations relate to community and physical links or barriers across the country. Finally, there are things the Commission is (implicitly) not allowed to factor in.

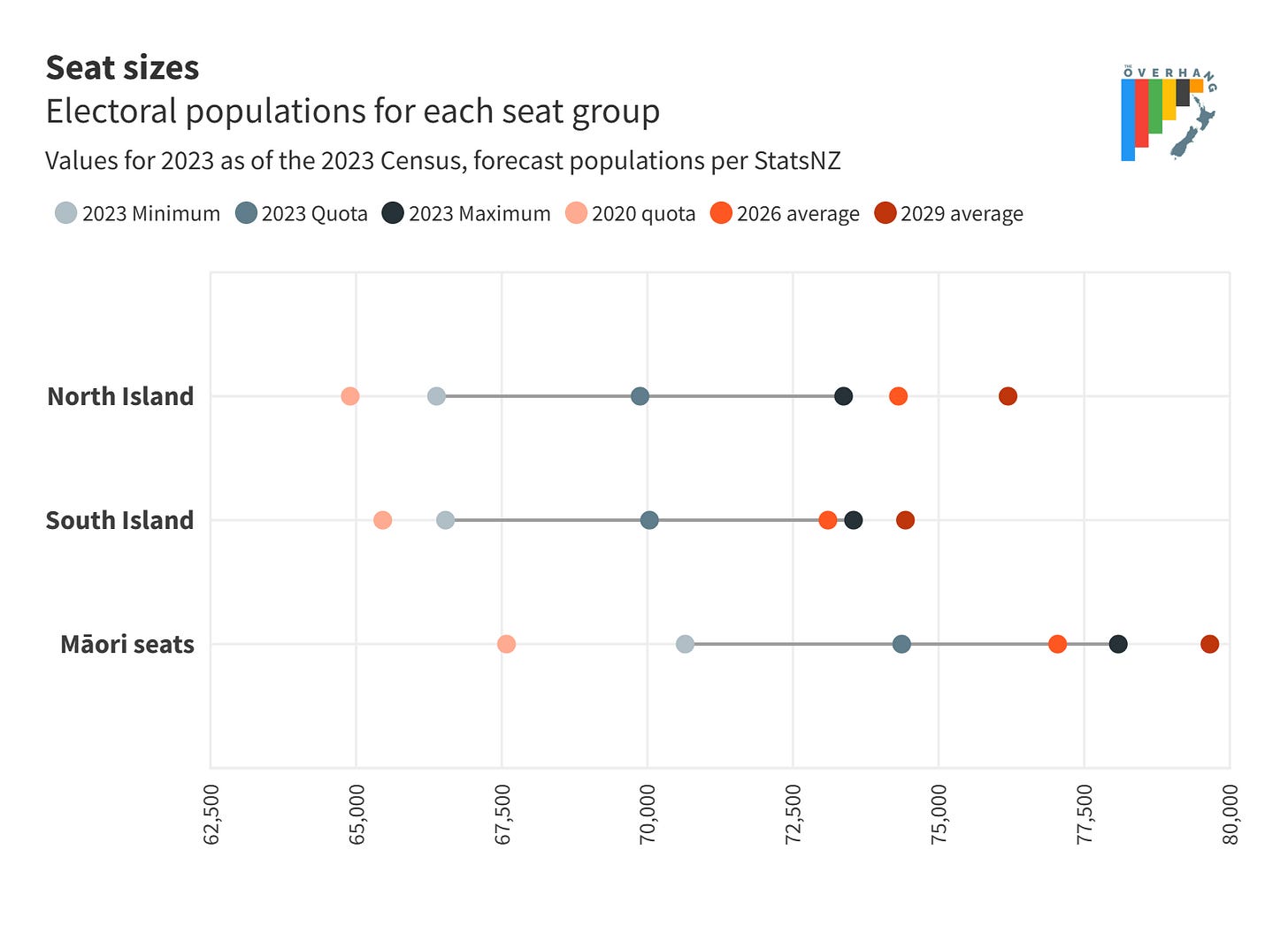

Quotas and tolerances

The quota is the average size of an electorate for each of the North Island, South Island, and Māori seats. Either side of this is a 5% tolerance.

The quota itself is a target rather than a requirement: it’s good if you can hit it, but if you have good reasons to depart from it, you can. The tolerances are mandatory: seats must fall within them, no exceptions.

To recap from the previous issue:

North Island quota: 69,875 (tolerance 66,381 to 73,369)

South Island quota: 70,037 (tolerance 66,535 to 73,539)

Māori seats quota: 74,367 (tolerance 70,649 to 78,085)

Existing boundaries

First on the list of what the Commission has to consider is the boundaries of the electorates as they stand. In practice this has meant using them as a starting point. Giving priority to existing boundaries is important because:

· It minimises disruption (and confusion) for communities and their representatives.

· It constrains the near infinite choices presented by a blank map.

· It helps foreclose opportunities for gerrymandering by limiting partisan innovations. This is only true to the extent the existing boundaries are fair, but given the fairly robust processes over multiple years, this is largely the case.

Communities of interest

Every kind of collective, geographically-rooted identity. The Independent Electoral Review used the paraphrase “a group united by shared interests or values”. These are as many and varied as the varieties of human life, including but not limited to:

Urban areas like towns, cities, or suburbs

Employment and commercial centres

Community facilities like schools, clubs, or marae

Ethnic or other identity communities

Local government boundaries at a regional, local, and ward level

For Māori seats in particular (though arguably not exclusively) hapu, iwi, and their rohe

To make this a little more tractable, we will tend to follow pre-defined geographies in our analysis: local government boundaries, the StatsNZ statistical area hierarchy, urban/rural area classifications, or Te Kāhui Mānhai’s Iwi Map.

In a lot of ways, this criterion could stand on its own. Communication and topography will where relevant give rise to community links. On the other hand, it gives wide discretion to the Commission. A lot of the arguments in the objections (consultation) process tend to focus on what gets to count as a community, what forms of collective identity get prioritised, and who gets to define them.

Facilities of communications

A somewhat old-fashioned term (the wording in the Act goes back to at least 1927) that basically boils down to infrastructure that links communities. Historically, this might have included postal facilities and print or broadcast media markets. With ubiquitous, geography-less digital communication, it now essentially means transport infrastructure:

Most importantly road links, as physically-adjacent parcels of land may be not be connected by road (topographically close, but not topologically close).

For island communities, ferry links like those between the Hauraki Gulf islands and Auckland Central or Rakiura/Stewart Island and Invercargill.

For Rēkohu/the Chatham Islands, airports and specifically the link to Wellington airport (in the Rongotai electorate).

Arguably it could also include public transport corridors, but to my knowledge this has never been used as a basis for a boundary since at least 1996 (as far back as I checked).

Topographical features

This includes natural features like mountain ranges, rivers, coastlines, or forests, but also human structures like motorways or railways. Usually these present barriers (reasons to separate areas) but in some cases (valleys, islands) can give reasons for keeping areas together.

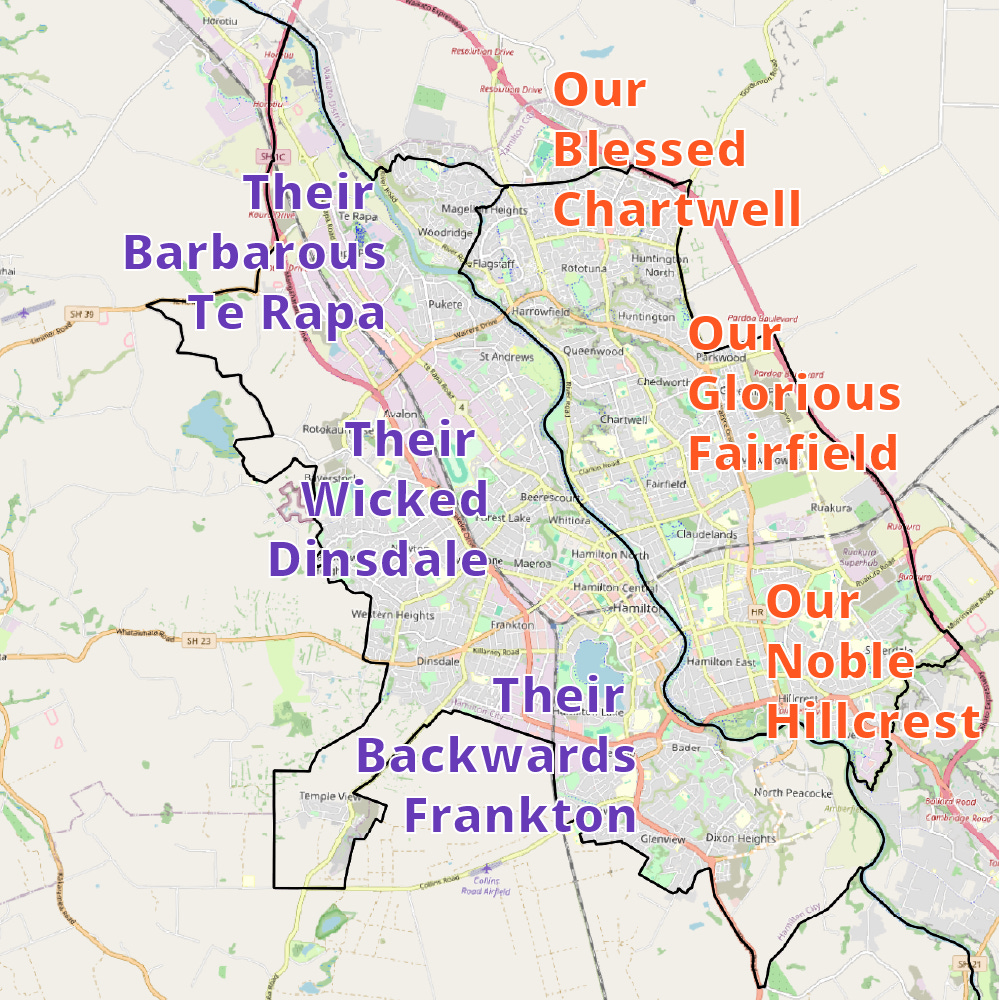

The most prominent example is the Main Divide along the spine of each island. You also see it on a smaller scale like dividing Hamilton largely by the Waikato River, or keeping the two Hutt electorates contained to the valley.

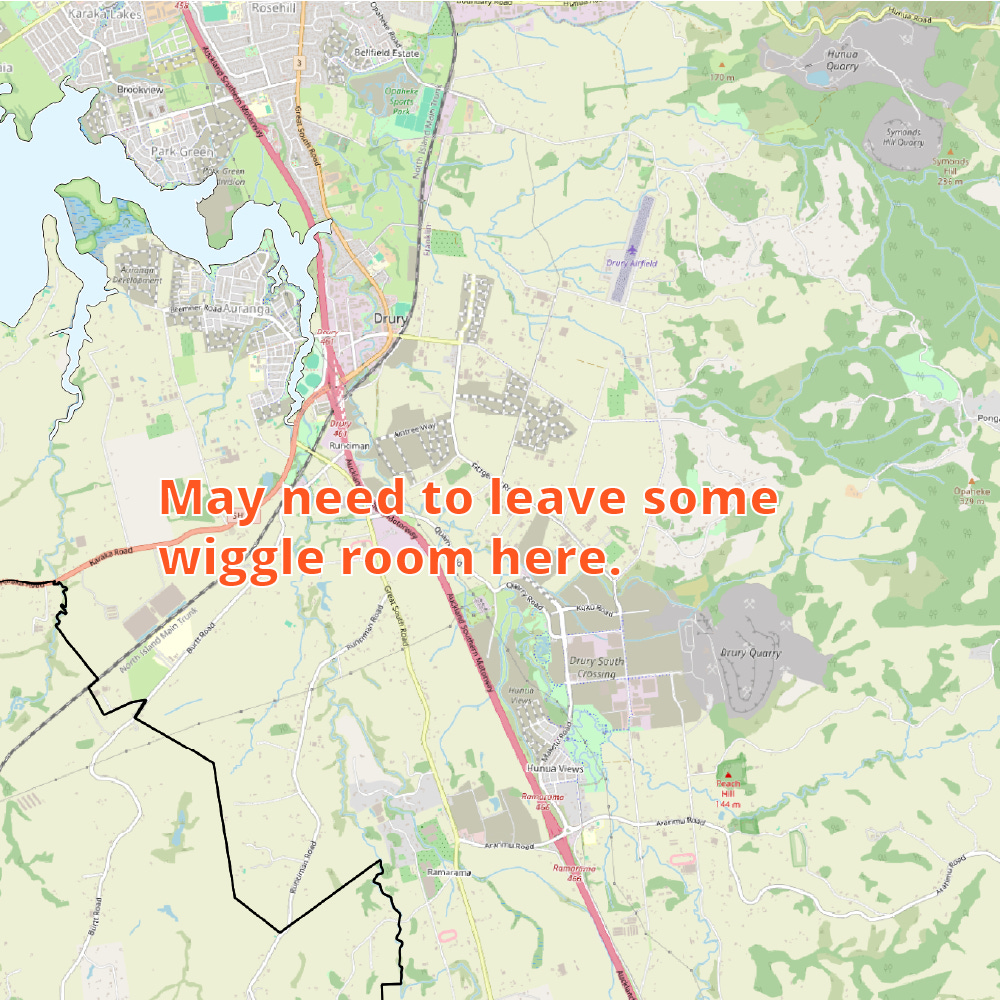

Forecast population changes

Finally, as well as current population the Commission can consider how the population is forecast to change over the life of the electorates (essentially until the next Census).

In most cases this will mean erring on the high side of the quota in shrinking areas or the low side in growing ones.

Irrelevant considerations

Beyond the defined list of factors, the Commission is permitted to consider anything else.

This means excluding partisan political matters. Obvious things like voting patterns or the residences of incumbent MPs are clearly off the table. But so are things like ‘proportionality’ (the results in electorates approximately mirroring the nationwide vote) and ‘competitiveness’ (making seats that give more than one party a decent chance). These can be important and legitimate for FPP systems, but are not an issue under MMP where the party votes takes care of things.

Not that any of this will stop parties and candidates submitting on the process from worrying about the effect on them. But they still need to frame any arguments in statutory terms.

It also excludes ‘aesthetic’ considerations like size, compactness (the ratio of area to perimeter: a measure proffered as an algorithmic cure to the USA’s cursed partisan redistricting processes), or shape (seats can look ‘weird’ provided they follow the rules).

Philosophical choices

There’s the rules as they’re written, and then there’s the rules as they’re applied.

Boundary-drawing is an art as much as a science, and the Commission (or anyone else involved in the process) has decisions to make about how to resolve tensions between the factors they’re required to consider.

To simplify how this judgement might be applied, I’ve broken things down into three broad trade-offs:

Existing boundaries vs optimal boundaries

Quota-targeting vs tolerance-targeting

Present focus vs future focus

When predicting, analysing, and critiquing the work of the Commission, we will try to do it through the lens of these choices.

Existing boundaries vs optimal boundaries

As mentioned above, past Commissions have generally started with existing boundaries and then made adjustments at the margins.

This is a legitimate choice, but it is still a choice.

The alternative is to start with defining communities of interest, looking at the geography that divides or unites them, then assemble them into sensible units. This is more difficult and more disruptive, but can avoid path-dependence and a calcified status quo.

As for all three axes, rather than two mutually exclusive approaches these are poles on a continuum.

If you will permit me to lapse from analysis into opinion for a moment – I think past Commissions have been unduly conservative in their approach and too deferential to existing boundaries. This can lead to perverse (albeit sometimes unavoidable) outcomes. We will get to some examples later in the week, but the split of Queenstown and Wānaka or the stretched mess of Taranaki-King Country come to mind.

Given the scale of disruption already necessitated by the number of electorates outside tolerance and the loss of a seat, this go around could present an opportunity for some much-needed rationalisation. But that’s hard and controversial, so I don’t see it happening. For the purposes of previewing changes, we’ll assume the Commission strongly favours existing boundaries.

Quota-targeting vs tolerance-targeting

This choice is about whether you’re aiming for the quota target, or whether you’re just trying to sneak inside the tolerance limits. The 2020 review staked out a clear minimalist position given the issues with the 2018 Census and the disruption of COVID.

For the purposes of analysis, we’ll assume the Commission takes a moderate quota-targeting approach (still not aiming for perfection, but less willing to accept exceedances than in 2020).

The minimalist approach is easier: do as little as you have to and leave less for people to object to. On the other hand, especially at the draft decision phase more thorough quota-targeting can both flush out what communities people care about and leave room to make changes in response to objections.

Too conservative an approach also risks stocking up problems for future reviews which brings us to…

Present focus vs future focus

How much you solve the problem in front of you versus how much you solve tomorrow’s problems. Too much focus on the present and your boundaries are stale by the time you use them and you leave a mess for the next guy. Conversely, predictions about the future are necessarily speculative and growth patterns over the medium term are fickle.

You can square this circle by erring on the high side for areas in long-term decline and on the low side in areas of higher growth.

Given the distance between the Census and the first election where the seats will be used (three years, about the longest gap you could have) there’s a good case for a slightly more future-focused approach than in the past.

You could bundled this distinction in with the quota/tolerance choice above, but as we’ll get into tomorrow, the degree of future focus matters a lot when choosing which seat to remove.

A long, bumpy string

Despite all these requirements, considerations, discretions, and philosophies in the end we are all slaves to context.

The over-riding reality is that Aotearoa is a long, skinny country divided by mountains.

This means that in a lot of cases you simply don’t have a lot of choice about where the boundaries go. The seats are laid out in chains between the mountains and the sea (or the sea and the sea) and the boundaries are (within certain margins) just a matter of where the people are.

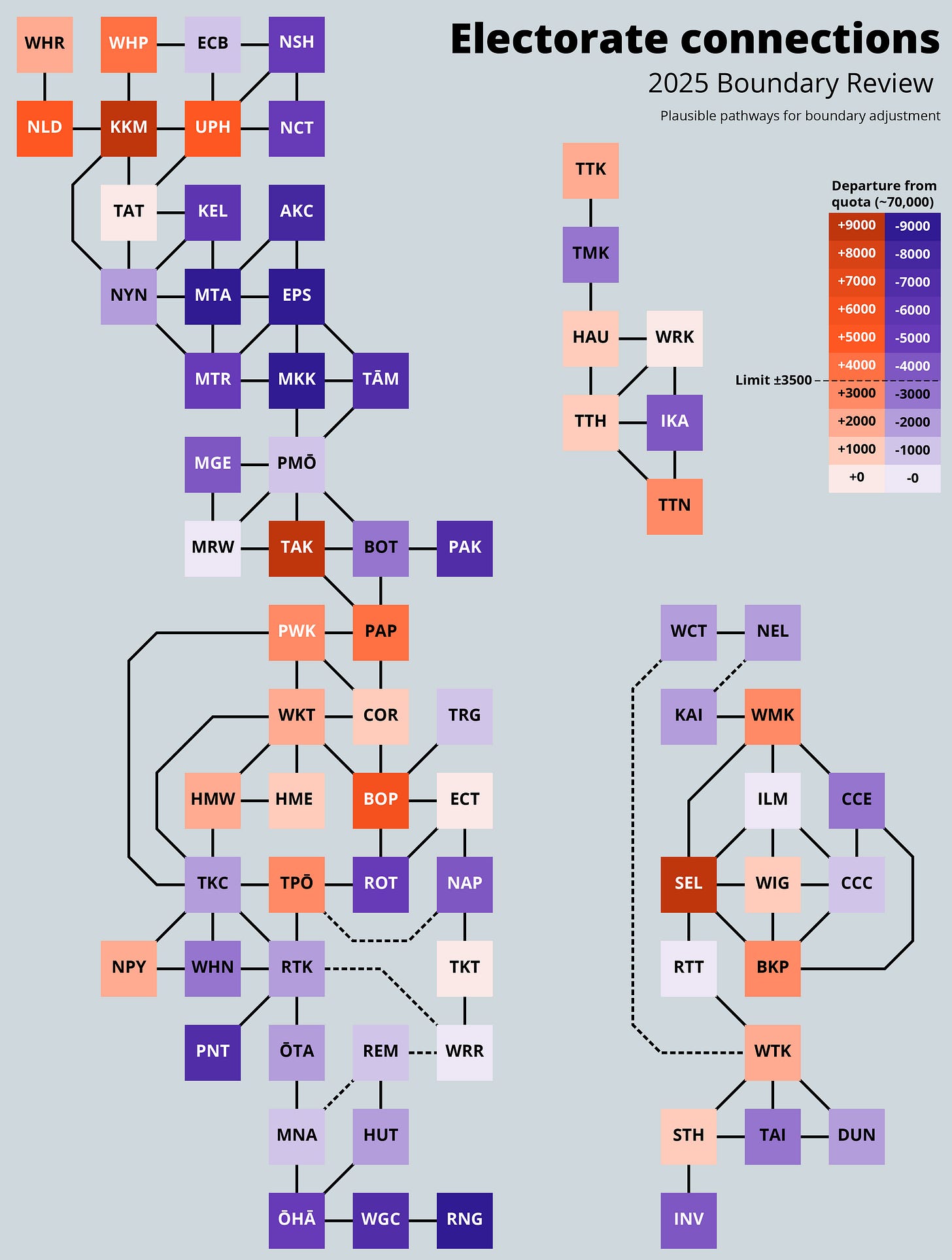

Which is as good a way as any to introduce this monstrosity: the Electoral Sefirot. I know it’s a lot, but believe me when I say it’s a surprise tool that will help us later.

The graph shows:

Each of the current electorates and their connections to their neighbours.

Orange electorates are over quota, purple ones are under quota.

Electorates with white text are outside tolerance.

Solid lines show boundaries where an adjustment can be made without real difficulty

Dashed lines show boundaries where you could at a stretch make an adjustment (given transport links) but that where physical barriers mean you should try to avoid it.

Basically, the boundary review is a puzzle-box game where you have to:

Choose one box in the North Island to get rid of; and

Shovel people along the lines from the areas of surplus to the areas of deficit until you’ve complied with the rules and submitters stop yelling at you.

Right. With all the groundwork out of the way, we’ll be back tomorrow at start actually looking at how things might go.

Ka kite āpōpō (or maybe Thursday)